Back in 1910, the United States used the terpene thymol to eradicate hookworms. [1] Such practices were discontinued due to the intense side effects that came along with consuming too much. However, recent research is looking to back up these old efforts with modern methods.

Currently, benzimidazoles are the only class of drug used to treat soil-transmitted nematodes (STN), which infect between 1 to 2 billion people across the globe. The difficulty here is, given the scale of the problem, benzimidazoles must be distributed with mass drug administration (MDA). Only one drug within the class, albendazole, has been found suited for administration to entire target populations, but it has mixed efficacy against different species (which may also be resistant).

Terpenes have a long history of medicinal use and recent research has found them to have insecticidal, antifungal, and antibacterial properties. [2] This includes monoterpenes (e.g., cymene, limonene, and pinene) and terpenoids (e.g., terpineol and thymol). While major organizations such as the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) don’t approve terpenes for medicinal use, these molecules are already widely used in food, wellness products, cosmetics, and sectors of the pharmaceutical industry.

Recent research used yeast particles (YPs) to encapsulate high concentrations of terpenes. And through this, terpenes hold the potential to help cure STNs.

The authors explain that yeast particles are “hollow, porous microparticles (3–5 µm)” with adsorbent properties. Terpenes can be loaded into the YPs with passive diffusion. Seventeen YP-encapsulated terpenes along with three YP-encapsulated essential oils were studied against four parasitic worm species in vitro: the human hookworm parasite Ancylostoma ceylanicum, the murine whipworm Trichuris muris, the rat parasite Nippostronglyus brasiliensis, and albendazole-resistant Caenorhabditis elegans.

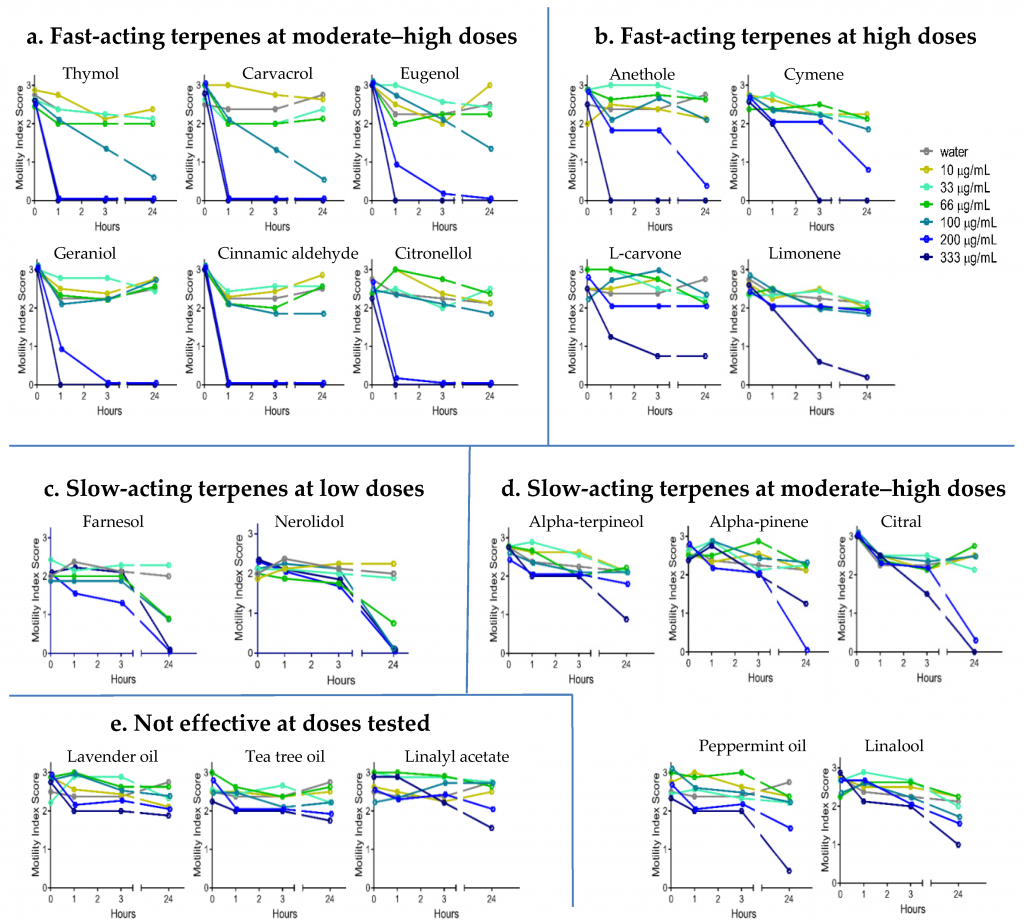

Terpene concentrations ranged from 0–333 µg/ml. The study found that even though not all terpenes had an effect on the parasitic worms, most did show promising results. Terpenes with fast action (1-3 hours) at moderate-high doses—the most efficacious—included carvacrol and thymol. These even overcame C. elegans.

In high doses, α-pinene and citral effectively fought against the parasites A. ceylanicum and T. muris at a slow (24 hours) but effective rate. Terpenoids farnesol and nerolidol also acted slowly but at low doses. Essential oils were not considered effective. Terpene efficacy against A. ceylanicum is summarized in the graphs below, reprinted from the open-access study.

Terpene YPs against A. ceylanicum. Reprinted from: Mirza Z, et al. Anthelmintic activity of yeast particle-encapsulated terpenes. Molecules. 2020;25(2958). License: CC BY 4.0.

Interestingly, the researchers suggest that parasites react differently to the terpenes. A. ceylanicum seems to absorb the YPs and, once released inside the worm, the terpenes exert deadly effects. However, T. muris doesn’t appear to ingest YPs at all; rather, the terpenes release into the medium and are absorbed by the worms.

“Terpenes are predicted to be extremely difficult for parasites to resist,” the authors note. The YPs “could lead to the development of formulations for oral delivery…”

Photo by Thomas Kinto on Unsplash.

References

- Mirza Z, et al. Anthelmintic activity of yeast particle-encapsulated terpenes. Molecules. 2020;25(2958). [Impact Factor: 3.267; Times Cited: 1 (Semantic Scholar)]

- Lupoi, J. The Cannabis Terpene Experience. Mace Media Group: Pismo Beach. 2020.