The joint may be the most iconic symbol of cannabis consumption. It’s a trinity of paper, cannabis, and fire, forged by human hands, shared by kindred souls. Simple and unassuming, the joint transcends barriers. Its humble powers enchanted 19th century Mexican laborers, 1920s jazz musicians, Rastafari devotees, counterculture visionaries, and American soldiers in Vietnam. Today, the legacy of the joint continues for contemporary medicinal and adult use consumers.

Intuitive, subjective, and clandestine uses of cannabis — although beautiful from a cultural perspective — do not translate well to scientific standardization. In 2017, several researchers decided to investigate the anatomy of a joint. [1]

They recognized the problem associated with frequency of use self-reporting in most cannabis studies: there is no “standard unit” of measurement. Hand-crafted joints are almost certain to be unique, conferring widely variable doses. Despite the questionable accuracy of self-reported estimates, they largely inform public health research.

In Europe and other countries outside the US, joints are often co-wrapped with tobacco, further complicating the anatomy of a given joint. These are also commonly referred to as spliffs. According to the researchers, nicotine may increase delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) release and alter the cognitive effects experienced.

The study authors designed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover experiment. Based in London, they recruited regular users (> once/month, but < than 3 times/week) of mixed cannabis and tobacco joints. The “crossover” aspect of the design went four ways, meaning all participants (12 females and 12 males) were subject to four combinations of two ingredients:

- Cannabis: 66.67 mg Bedrobinol, 16.1% THC

- Tobacco: 311 mg Marlboro red, 15.48 mg nicotine

- Placebo cannabis: 66.67 mg Bedrocan, 0.07% THC with matching terpene profile

- Placebo tobacco: 311 mg Magic 0, 0.04 mg nicotine

Researchers started with a baseline assessment. They placed two king-sized rolling papers in front of participants, along with tobacco and cannabis, and asked them to roll the joint how they usually would if they were planning to “smoke the whole joint by themselves.” Participants then guessed (by sight) how many grams of cannabis and tobacco they had used. Actual amounts were weighed to the nearest 0.01 grams.

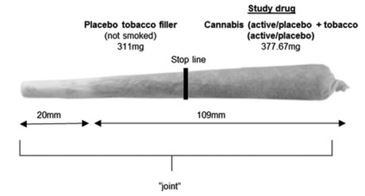

For the four experimental joint conditions, the researchers guided the participants’ inhalation/exhalation patterns and restricted consumption to precise amounts (see image).

With 30 second breaks between puffs, participants smoked the joint to the stop line. Then they waited for one hour. At the 1-hour mark, they were asked to roll a joint with the quantities of cannabis and tobacco they felt like smoking “right now.” Again, the participants estimated how many grams they had added. Researchers then weighed the actual amounts.

Participants overestimated how much cannabis they had added by about 200% across baseline and all experimental conditions. However, they were accurate with tobacco estimates across all conditions. After smoking active cannabis, subjects added significantly less cannabis and tobacco at the 1-hour mark. Compared to placebo cannabis, active cannabis improved subjects’ estimates of tobacco at the 1-hour mark. Active tobacco, on the other hand, did not influence any condition.

In summary, the researchers point out that “overestimation of cannabis and accurate estimation of tobacco amounts are a reliable finding and impervious to acute intoxication with cannabis

or tobacco.” Their experimental design, which they call the “Roll a Joint Paradigm,” could present a solution to “inaccuracies when collecting cannabis use metrics.” [1]

Reference

- Hindocha C, et al. “Anatomy of a Joint: Comparing Self-Reported and Actual Dose of Cannabis and Tobacco in a Joint, and How These Are Influenced by Controlled Acute Administration.” Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, vol.2, no.1, pp.217-23. Times Cited = 8.