You may have noticed in the last three or four decades that popular varieties of cannabis are commonly known as strains. But there are better terms available.

Strain is a nuanced word with an assortment of definitions. In bacteriology, strains are descendants of an isolated colony selected from a pure culture; in other words, they are isolated genetic variants of bacteria. [1] Encylopedia Brittanica extends a similar definition to domestic animals in a “true-breeding, genetically pure line.” In 1954, Roll-Hansen [2] took a stab at the word strain for botany, suggesting it could refer to a pure line or family (self- or cross-pollinated) of plants within the same cultivar. Breeders and plant geneticists used (and continue to use) the word this way, unofficially indicating an individual plant or direct line of plants with genetic variation that may or may not be desirable. [3,4]

The International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants, 8th edition (ICNCP) defines strain as: “a confused term having several meanings; in cultivated plant nomenclature: often referring to a seed-raised cryptic variety.” Cryptic variety refers to cultivated plants that are not sufficiently distinct to warrant taxonomical separation from their respective cultivar. [5]

A viral ‘strain.’ Cybercobra, CC BY-SA 3.0

In the cannabis sphere, the word strain popularly encompasses the entirety of a specific plant and product, from the duration of its vegetative period to how the cured flowers affect consumers. But taken from its original context, the word lacks meaning, no longer reflecting even genotype. A 2015 study genotyped 81 medical cannabis samples, pointing out that “[cannabis] strain name does not necessarily represent a genetically unique variety,” and “strain names often do not reflect a meaningful genetic identity.” [6] A 2017 study looked at over 2,600 samples from Nevada and narrowed down 396 “strain names” to 12 distinct genotypes. [7]

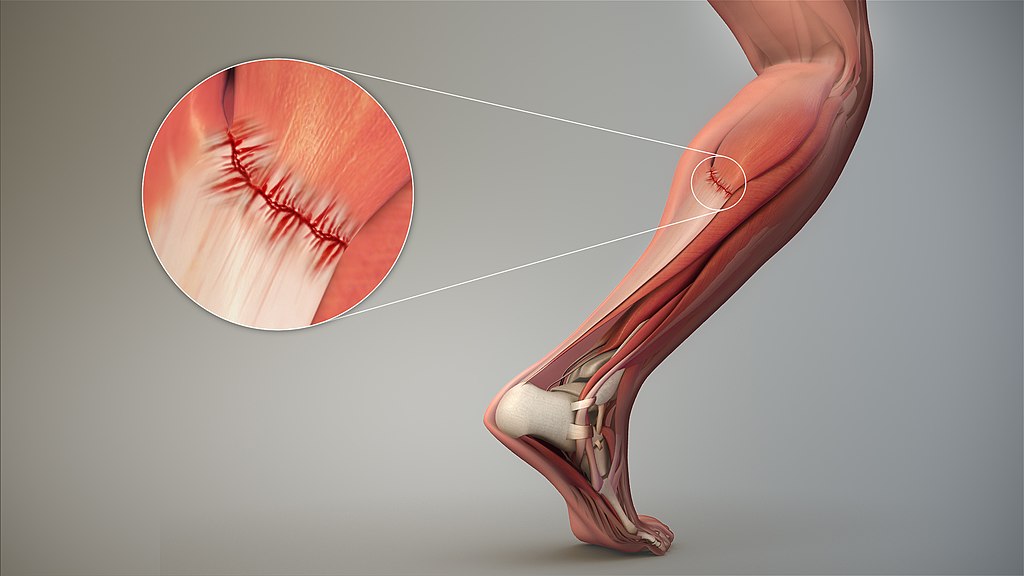

A tendon ‘strain.’ Scientific Animations, CC BY-SA 4.0

One analyst suggests that the clandestine nature of the cannabis industry for many decades led to the perpetuation of strain many generations beyond pure plant lines.

More accurate nomenclature is cultivar, a portmanteau word for “cultivated variety.” The cultivar is a horticultural classification referring to plants within the same species that are intentionally propagated to feature a distinct, stable set of shared characteristics.

The ICNCP lays it out as such:

“A cultivar is an assemblage of plants that (a) has been selected for a particular character or combination of characters, (b) is distinct, uniform, and stable in these characters, and (c) when propagated by appropriate means, retains those characters…” [5]

This definition includes propagation through cloning, hybridization, and/or distinct origin so long as it “maintain[s] the characters that define a particular cultivar…” [5] Roll-Hansen [2] suggested that a cultivar may contain multiple strains that fall within its range of characteristics.

For example, Leafly describes cannabis variety Maui Wowie with descriptors that include: “sweet pineapple flavors,” “high-energy euphoria,” motivating, active effects,” and “tall, lanky… best suited for cultivation in warm, tropical climates…” These are stable distinctions — consistent chemical and physical characteristics — that give Maui Wowie an identity as a type of cultivated cannabis plant.

In lieu of cultivar, plant taxonomy offers the word variety (var.) as a classification after species and subspecies, but this definition does not stipulate human cultivation. The International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants does not accept this usage for horticultural purposes. [5]

There are other approaches to cannabis taxonomy that aim to solve this dilemma from the perspective of plant chemistry.

Until next time, we can conclude that cultivar triumphs over strain, and it’s not just to sound smarter. The word cultivar matches reference to the varieties of cannabis propagated internationally for their stable and desired characteristics.

References

- Dijkshoorn L, et al. “Strain, Clone, and Species: Comments on Three Basic Concepts of Bacteriology.” J Med Microbiol, vol.49, 2000, pp.397-401. Journal Impact Factor = 3.362, Times Cited = 47

- Roll-Hansen, Jens. “Definition of the Terms Cultivar and Strain.” Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, vol.4, no.1, Taylor & Francis, 1954, pp.237–38, doi:10.1080/00015125409439939. Journal Impact Factor = 0.810

- Bailey LH. The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture, MacMillan, 1914, Google Books.

- Woo S, et al. “The Development of New Soybean Strain with ti and cgy1 Recessive Allele.” J Plant Biotechnol, vol.45, 2018, pp.328–332.

- Brickell, CD, et al. “International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants. 8th Edition. [Scripta Horticulturae 10].” Regnum Vegetabile, vol. 151, 2009. Times Cited = 15

- Sawler J, et al. “The Genetic Structure of Marijuana and Hemp.” PloS One, vol.10, 2015, p. e0133292, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133292. Journal Impact Factor = 2.776, Times Cited = 87

- Reimann-Philipp U, et al. “Cannabis Chemovar Nomenclature Misrepresents Chemical and Genetic Diversity; Survey of Variations in Chemical Profiles and Genetic Markers in Nevada Medical Cannabis Samples.” Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., 2019, doi:10.1089/can.2018.0063. Times Cited = 2