“I took a walk in the woods and came out taller than the trees.”

– Henry David Thoreau

Forests guard untold magic. Walking through forests improves health and well-being—the Japanese call this shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing. [1] Trees and plants saturate forest air with terpenes that confer myriad benefits. Recently, researchers identified a series of forest terpenes and outlined their benefits against inflammation. [2]

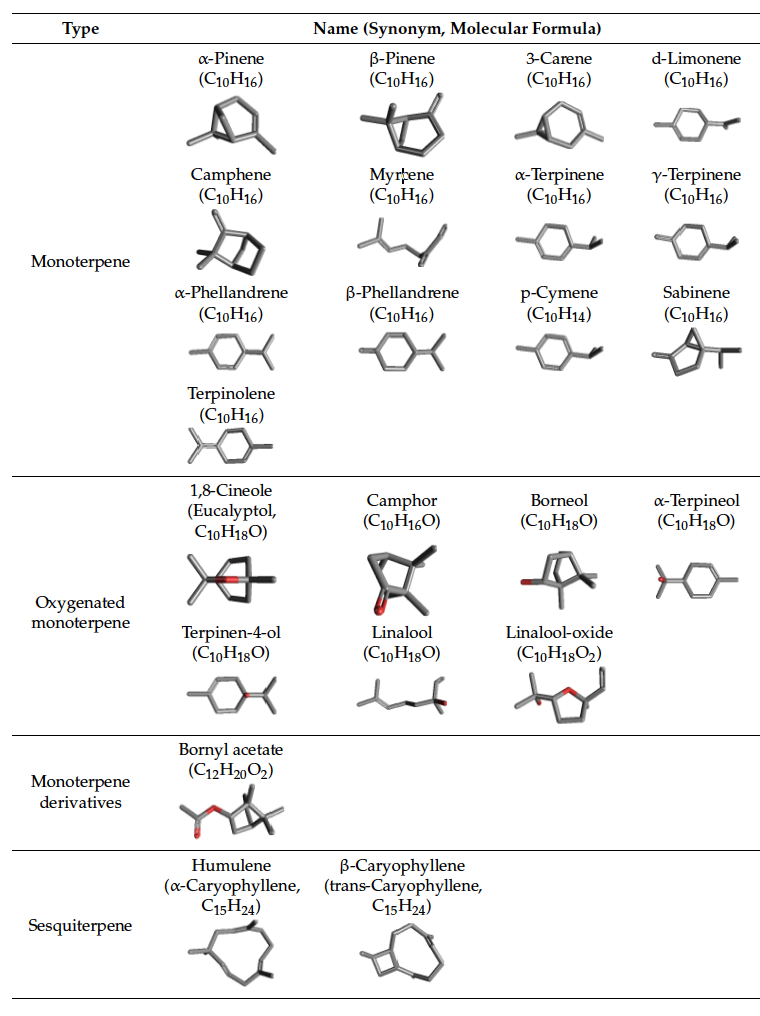

After reviewing forest emissions from North America, Europe, and Asia, they selected 23 terpenes: 13 monoterpenes, 7 terpenoids, 1 monoterpene derivative, and 2 sesquiterpenes (see image). They noted that inflammation, left unchecked, can lead to “acute and chronic inflammatory diseases causing excessive or long-lasting tissue damages.”

Forest terpenes primarily reduce inflammation by decreasing pro-inflammatory chemicals such as nitric oxide (NO), interleukins, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). For example, α-phellandrene has been shown to inhibit inflammatory mediators associated with lung injury. [3] In mouse brains with Alzheimer’s, linalool mitigated a number of inflammatory markers, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2). [4]

Terpenes also reduce inflammation by activating or inhibiting certain signaling pathways. Camphor [5] and limonene [6], for example, activate transient receptor potential vanilloids (TRPVs), which are “strongly implicated in inflammatory responses.” β-Caryophyllene activates the cannabinoid type 2 (CB2) receptor on immune cells, reducing inflammation as the dietary cannabinoid.

Oxidative stress can cause inflammation, and forest terpenes work as potent antioxidants. Generally, they hamper the enzymes that catalyze reactive oxygen formation or protect against oxidative damage (for example, by scavenging free radicals). The authors of the review note that most of the forest terpenes possess antioxidant activity, but they point out myrcene for widespread actions that indicate “potential application in the skincare industry owing to its protective effect on photoaging.”

Finally, terpenes such as limonene [7] stimulate autophagy, helping cells remove harmful elements such as tumors.

The researchers then shifted their review toward four inflammatory diseases: respiratory inflammation (asthma), atopic dermatitis (eczema), arthritis, and neuroinflammation. Among the aforementioned forest terpenes, they emphasized 12 with efficacy for these diseases, namely six terpenes, α-pinene, β-pinene, d-limonene, myrcene, α-terpinene, and β-caryophyllene, and six terpenoids, 1,8-cineole, camphor, borneol, α-terpineol, linalool, and bornyl acetate.

Some of the relevant terpenes for each disease include α-pinene for asthma since it is a bronchodilator at low concentrations. [8] As mentioned, myrcene “ameliorates human skin aging” and may thus help heal eczema. The authors note that among all forest terpenes, “β-caryophyllene has been reported as a good candidate to treat [rheumatoid arthritis].” β-Caryophyllene also stands out for its protective effects against neuroinflammation. Its activity on the CB2 receptor may help safeguard against neurodegenerative disorders. [9]

This is obviously complex. We are only beginning to understand the healing powers of terpenes in forests. Nonetheless, this research highlights the “beneficial effects of forest aerosols and propose[s] their potential use as chemopreventive and therapeutic agents for treating various inflammatory diseases.” [2]

References

1- Park BJ, et al.The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010;15(18). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-009-0086-9. [Impact Factor: 1.568; Times Cited: 535 (Semantic Scholar)]

2- Kim T, Song B, Cho K, Lee I-S. Therapeutic potential of volatile terpenes and terpenoids from forests for inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2187. doi:10.3390/ijms21062187. [Impact Factor: 5.923; Times Cited: 23 (Semantic Scholar)]

3- Siqueira HDS, et al. α-Phellandrene, a cyclic monoterpene, attenuates inflammatory response through neutrophil migration inhibition and mast cell degranulation. Life Sci. 2016;160:27–33. [Impact Factor: 3.647; Times Cited: 25 (Semantic Scholar)]

4- Sabogal-Guáqueta AM, Osorio E, Cardona-Gómez GP. Linalool reverses neuropathological and behavioral impairments in old triple transgenic Alzheimer’s mice. Neuropharmacol. 2016;102:111–120. [Impact Factor: 5.25; Times Cited: 57 (Semantic Scholar)]

5- Xu H, Blair NT, Clapham DE. Camphor activates and strongly desensitizes the transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 channel in a vanilloid-independent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8924–8937. [Impact Factor: 6.167; Times Cited: 343 (Semantic Scholar)]

6- Kaimoto T, et al. Involvement of transient receptor potential A1 channel in algesic and analgesic actions of the organic compound limonene. Eur J Pain. 2016;20:1155–1165. [Impact Factor: 3.492; Times Cited: 21 (Semantic Scholar)]

7- Yu X, et al. d-Limonene exhibits antitumor activity by inducing autophagy and apoptosis in lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:1833–1847. [Impact Factor: 3.492; Times Cited: 47 (Semantic Scholar)]

8- Falk AA, et al. Uptake, distribution and elimination of alpha-pinene in man after exposure by inhalation. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990;16:372–378. [Impact Factor: 4.127; Times Cited: 100 (Semantic Scholar)]

9- Youssef DA, El-Fayoumi HM, Mahmoud MF. Beta-caryophyllene alleviates diet-induced neurobehavioral changes in rats: The role of CB2 and PPAR-γ receptors. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;110:145-154. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.039. [Impact Factor: 6.529; Times Cited: 22 (Semantic Scholar)]

Image by Free-Photos from Pixabay